UConn’s Mike Zacchea Describes Many Challenges He Faced as First U.S. Military Adviser to New Iraqi Army

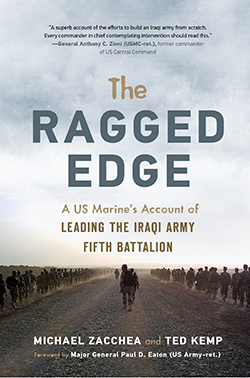

In his new book, “The Ragged Edge,” set for release on April 1, U.S. Marine Lt. Col. Michael Zacchea ’12 MBA shares the staggering hardships and unique challenges of the U.S. mission to build an Iraqi Army virtually from scratch.

In the wake of the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, Zacchea eagerly accepted his assignment as the first U.S. military adviser to build, train and lead the Iraqi Army.

But what Americans saw on television and read in the news in 2004 was often a distortion of what was occurring in Iraq, said Zacchea, now the director of the School of Business’ highly successful Entrepreneurship Bootcamp for Veterans with Disabilities (EBV) and a tireless advocate for veterans.

His book offers a unique perspective on the fledgling soldiers of Iraq, the daunting challenges of the mission, and the U.S. intelligence void that ultimately contributed to our country’s ongoing military involvement and the war’s disappointing results. The book ranges from fascinating and insightful to brutal and horrifying.

Much of the violence that Zacchea witnessed or heard about was too gruesome to include, he said. What he learned in Iraq has made him a staunch opponent of torture, under any circumstances.

In “The Ragged Edge,” Zacchea explains the religious divide that threatened to splinter the new army and details the insurgent movement that ultimately gave rise to ISIS.

But Zacchea’s book is more than just an introspection of a challenging military operation. In “The Ragged Edge,” Zacchea, the recipient of two Bronze Stars, the Purple Heart and Iraq’s Order of the Lion of Babylon, describes the physical and psychological toll that war takes on a military leader. He also shares his powerful saga of personal bonds of friendship with Iraqis, the importance of investing the time to develop an understanding and appreciation of another culture, and an assassination plot that could have claimed his life.

A book signing is planned for 6 to 8 p.m. April 25 at the Graduate Business Learning Center in Hartford. Proceeds from books sold that evening will benefit the EBV. For more on the book, please visit www.theraggededgebook.com.

Below is from a recent interview with Zacchea:

Your mission with the Iraqi Army Fifth Battalion in 2004-05, after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, has been described as like, “Trying to build an airplane in mid-flight.” How so?

I don’t think it was mission impossible, but there were many, many flaws. First, there were no ground assets—food, functioning toilets, equipment… we lacked many of the supplies that would be available to any military unit. We needed beds, boots, equipment, uniforms, radios and vehicles before we could even begin basic training, develop a cohesive, respectable, accomplished battalion, and prepare our strategy against the insurgents.

The food was not only badly cooked; it was tainted. Our cooks had never been taught to wash their hands before preparing food and on several occasions, many members of our battalion became very ill. There were soldiers who smeared human excrement on the walls as part of their worship practices. Our military unit included Zoroastrians that the Iraqis called “fire worshippers,” Yazidis, whom the Iraqis referred to as “devil worshippers” and various ethnic and religious groups, many of whom had a longstanding hatred toward each other.

On top of that, Iraqi soldiers were free to resign whenever they wished—we never knew how many military personnel we’d have on any given day. I think most Americans would be very surprised to learn of the challenges we faced.

From an intelligence standpoint, the U.S. had an abysmal lack of basic information about the Iraqis, their ethnicities, and their cultural divides, creating a potentially fatal lack of knowledge.

The Iraq War was more complex than any other because of the language, the religion, the propaganda, the culture and the brutal combat to which we were exposed. Some of these people in the Iraqi Army had fought U.S. forces—or against each other. It was a crazy situation. I’m not aware of any other advisory mission where they took ‘warring factions’ and tried to make an army out of them. Building an Iraqi Army was the strategic focus of the war, but at times it was incredibly complicated.

In addition to the danger of warfare, you personally were a wanted man by the Iraqi insurgents. In the book you wrote about your discovery of an assassination plot:

“I said nothing. That was more money than some Iraqis make in a lifetime. I thought about the note that showed up at the gate back in September: ‘The infidel Zakkiyah will die like the other dogs.’

…Ten minutes stretched and I paced the room. Questions bounded through my mind like startled deer. How deep did this go? Which Iraqi officers could I tell? How would the advisers on my team react? And there was the simplest, worst question: Who could I really trust?”

Did you ever think you would leave Iraq alive?

The night of the ambush that was supposed to claim my life, the thing that saved me was the trusting relationship I had developed with the Iraqis. They watched out for me; they protected me. Absent that, I think it would have been a very different outcome.

We didn’t know if the attack was real or a rumor…or what was going to happen. It was getting late, and they were late, and then it happened. We didn’t know if the insurgents would go out blazing or how committed they were to doing this. It was very nerve-wracking, and it continues to have an effect on me today.

The type of combat you experienced in Fallujah was unlike any other, because it involved storming buildings without having any idea whom you’d find inside. You wrote:

“Some were guerilla fighters, trained to attack but not eager to die. The second group was from al-Qaeda. They were foreign zealots who wanted to die and to kill Americans along the way. We had no way of knowing it at the time, but it was these men who years later would form ISIS.”

How do you survive the strain of that constant life-or-death situation?

It was unbelievable. There would be a hole in the ceiling of a home, and our adversaries would drop grenades through it. It is amazing I survived. It was luck of the draw. One of our reinforcements, a U.S. Marine, was killed clearing a house in a firefight with insurgents. He got shot twice in the head. They dropped a grenade and he swept it under his body and saved all the others. We all experienced stuff like that and I can’t account for it. The experience of being in a house, I actually don’t remember much of that. Your brain shuts down. It’s almost impossible to describe. Experiencing it is truly sensory overload.

You’ve spoken about the importance of the Iraqi translators and how critical they were to the U.S. mission. Can you tell me more about that?

For an American imbedded with the Iraqis you cannot overstate the importance of our translators. Our lives depended on the translators’ ability to not only translate what we said, but to share our cultural understanding. If we didn’t have them, there is no doubt we would have wound up dead. Often they took this challenge at tremendous personal cost. Their families were threatened, traumatized, brutalized and even murdered.

When you see the destruction, the toll that this war has taken on Iraq, what do you think?

In the last decade, Iraqis would tell me we had done more damage than the Iran-Iraq war did, which had tremendous casualties, some half million people. But even then the society held together. The economy didn’t get destroyed. We’ve destroyed whatever Iraqi identity there was. There really is no such thing as Iraq at this point. Iraq is Baghdad, basically.

How long was “The Ragged Edge” book in the works?

I started writing it years ago, first in a New York University writer’s workshop, and, later, as part of a cognitive behavioral therapy. In 2008, I placed an ad on a writer’s website and chose Ted Kemp, now a senior editor at CNBC, as my co-author. I think when you’re experiencing an event, you don’t see all the things that are going on. Only later did we see the rise of ISIS, the fall of Fallujah. I wouldn’t have been able to write the story as soon as I got back. It is a complete story now. This is my story. This is my reality.

What is the lesson to be learned from your experience?

First, I think there are limits to our ability to promote democracy. Not everybody wants to be American or to have democratic elections. They have their own ideas, own values and unique understanding of the world and how the universe works. We can’t just go and tell them ‘This is how it is.’ At the same time, most people want some of the same things: a peaceful place to live, stability and the ability to give their kids a good life.

Another lesson I learned from the war is the importance of political vigilance. I told the mayor of Fallujah that thousands of people were dead because of his cowardice. We saw the Iraqis first election in January 2005, and I think about that versus how only one-third of Americans are willing to vote. They say things like, “Oh I didn’t go because it was raining.” Americans don’t risk their lives to vote. We often take that privilege for granted. People need to be politically involved.