When Steve Graf, and dozens of fellow volunteers, traveled to Ghana to help the sick, they brought 35 suitcases of medications and provision—and an endless supply of good intentions.

After a week of triaging patients, and distributing medications, Graf and his colleagues made a startling discovery. Many of the patients weren’t recovering, and some were consuming medications too quickly.

Some adults were doubling up on blood-pressure medications. Children were guzzling liquid acetaminophen from the bottle. And, compounding the problem, many of the patients were illiterate. Sometimes parents would leave the clinic with as many as 20 different prescriptions for their four children, leading to endless confusion.

Everyone on the medical mission was frustrated with the situation, but Graf just couldn’t let it go.

“I thought, ‘This is a terrible thing. I don’t understand how this could be,'” he said. Graf, now a UConn senior majoring in healthcare management, thought about the problem often after he returned from the trip in May of 2013.

How do you give clear and memorable instructions to someone who can’t read? The clinic had tried using illustrations, showing a sun or a moon, but that didn’t seem to work.

“We approach problems given our education and training,” Graf said. “Because we learned to read at age 6, we absorb information visually. Illiterate folks do not. Their traditional learning is verbal.”

Graf thought if the prescribing physician could give medical instructions using an inexpensive recording device, like the one found in a musical greeting card, patients would be able to more easily follow dosing instructions.

He mentioned that concept one day in front of friend Charles Fayal, now a UConn senior majoring in molecular cellular biology and biomedical engineering.

“The moment I heard the idea, I got pretty excited because I instantly knew how beneficial the prescription device could be—and how simple the idea is,” said Fayal, a Stonington native. “It’s funny how somebody else’s excitement spreads, because when I got excited about his idea, Steve got more excited. After that moment we knew we had to pursue this journey.”

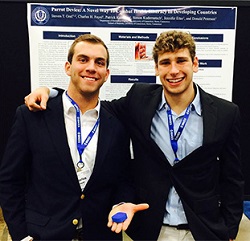

After a great deal of research, experimentation and cost analysis, Graf and Fayal have found an inexpensive recording module, manufactured by a Chinese company, that they will be using as their first prototype. The “Parrot Device,” as they’ve nicknamed it, will allow a medical expert to record up to 60 seconds of medical instructions. The casing could be color-coded to match the medications, and both would be placed together in a travel bag.

Neither Graf not Fayal is looking for profit—or even much recognition. A successful solution, they both said, would be rewarding enough.

“We’re hoping this will save lives. That means everything to Charles and me,” said Graf, of Westport, who is the president of the UConn chapter of Global Brigades, a student-led organization that provides medical, public health, clean water and environmental relief trips to countries such as Ghana, Panama, Nicaragua and Honduras.

Graf and Fayal presented their idea at the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) annual meeting in San Antonio recently. It was well-received there, as it has been by physicians who are familiar with the challenges of working in third-world nations.

The biggest challenge for the two entrepreneurs has been keeping the price reasonable. Right now it is about $2 per device, and with a large order can probably be dropped to $1. Graf said he would like to try to get the price even lower. The cost of AIDS or blood-pressure medications can be several dollars per day, Graf said. The cost to resolve damage done by consuming prescriptions too quickly—or slowly—can be several times that, he said. The cost-versus-benefit of the Parrot Device is the focus that Graf and Fayal need to persuade organizations interested in their project.

Graf got his start-up funds for the project by winning a Connecticut Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation pitch competition last year, which gave him $1,000 in seed money for the sound modules and plastic mold for the casing. He and Fayal are now seeking funding for a January trip to Haiti to test the device with patients.

“Haiti is somewhat of a make-or-break trip for us,” said Graf. “We hope to test our prototypes. Our main questions are, ‘Will the patients use the device as intended? Will the community adopt it? Will the patients benefit from it?'”

Beyond the initial concept, Graf and Fayal envision additional uses, such as education in infectious disease areas, such as Ebola-plagued villages. Prevention might become an even greater tool than treatment, they said.

Next semester Graf will take an entrepreneurship class and plans to write a business plan focused on the device. Graf and Fayal are hoping a large charitable organization will adopt the cause and fund the project.

“It has been a journey bringing this device to fruition,” Fayal said. “Some days we’ll realize that we have a mound of work in front of us, or a major obstacle to tackle regarding manufacturing or approval.

“On these days we get bummed out, but we know we have to power through because when we get to talk to somebody who has been to a place where this device is useful, it makes it all worthwhile. These people, whether they grew up in an impoverished area or worked in one, will get excited about the idea,” he said. “Just like when Steven first told me about the idea, we get excited about it all over again.”