Many people think of the human brain as like a giant filing cabinet. Just open the right drawer, pull out a folder, and it will be loaded with all the information you need.

Many people think of the human brain as like a giant filing cabinet. Just open the right drawer, pull out a folder, and it will be loaded with all the information you need.

In fact, retrieving information is more like going on an archaeological dig, said G. Christian Jernstedt, professor emeritus of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth College.

“We find fragments and we assemble them into something meaningful,” he said. “That’s why we rummage around in our brains for the answers. Sometimes there isn’t even a correct answer. It’s the thinking that is the important part.”

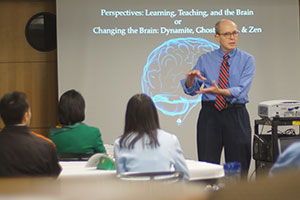

Jernstedt spoke to 60 faculty and graduate students Oct. 31 at a workshop titled, “Perspectives on Learning, Teaching and the Brain.” Jernstedt specializes in human learning and speaks around the world about cognitive, social, behavioral and educational neurosciences.

During the full-day workshop, he talked about emerging research on increasing the ability to learn, building effective learning habits, and different ways to evaluate what has been learned.

Management Professor Travis Grosser said the lecture was fascinating. “I wanted to learn more about how the brain works and how to apply that knowledge in the classroom,” he said. “I appreciate that the School of Business is helping us become better teachers and helping us grow and develop our professional skills.”

Some 150,000 articles and books have been written about the human brain in recent years, Jernstedt said. Among his findings is that the more engaged a person is, the more active their learning becomes.

“Memory is constructed, it isn’t a passive situation. If it is an active process, it works,” he said. “The person who is ‘doing’ is the person who is learning.”

That’s why taking notes is more effective than listening; why talking to others is better than learning alone, he said.

What happens when you use an area of the brain a great deal? Before GPS was widely used, London cabbies had to study maps of the city until they knew every road. For them, the centers of the brain that learn place, direction and navigation blossomed. “When you use the brain, it changes,” he said.

But while some changes are universal, every individual learns differently. In fact, the human brain is a bit like a novelist, Jernstedt said.

“Our brain makes up stories about reality,” he said. “Our stories vary by experience. We all see things differently.”

For an example, he showed an abstract picture of a man and woman engaged in an embrace. When the same picture was shown to young children, they saw porpoises in the photo because their frame of reference is different, he said.

“So when we develop courses, programs and schools, it is important to recognize that how people code and retain information varies, depending what’s happened to them,” Jernstedt said.

The human brain contains 20 billion cells just for thinking, he said, yet we are most successful when we tackle one task at a time. “People who say they ‘multitask’ either do it poorly, or are really shifting between tasks,” he said.

Research by a jam-and-jelly company also indicates that too many options are overwhelming. On the days when customers could sample 20 or more types of jam, only 3 percent bought the product. When offered only five varieties, 30 percent of the customers purchased jam. Too many choices leads to indecision, he said.

In another analogy, Jernstedt noted that the tiger beetle runs about 5 1/2 miles per hour, but it does so in bursts, and then freezes, because its brain is filled up and it needs to rest it. Likewise, it is important for humans to take intellectual breaks in the classroom, and for faculty to build in time for students to process and reflect, he said.

The human brain is a powerful tool, he said. “This organ can do extraordinary things when we find out how to use it,” he said. With practice, people can even change the speed at which the brain operates.

Marketing Professor David Norton said he attended the workshop because he was interested in strategies to help his students. “We are asking them to learn a great deal in a rather short amount of time,” he said. “I’m interested in anything that helps to communicate that information more efficiently.”

“The biggest opportunity is to bridge science with practice,” said Management Professor Kevin Thompson, noting that students tend to retain only about 10 or 15 percent of what they hear in a lecture. “I’m here to find out what we can take away to help or improve learning for our students.”